Thomas Bewick

Date of birth

12 Aug 1753

Date of death

08 Nov 1828

Place of birth

Place of death

Biography

THOMAS BEWICK: A CHRONOLOGY

1753 Born at Cherryburn, Eltringham,

Northumberland, to John (farmer and tenant

collier) and Jane Bewick. Eldest of four sons

and five daughters.

1763-67 Attends school of Reverend C. Gregson at

nearby Ovingham Parsonage.

1767 Apprenticed to Ralph Beilby (1743-1817),

engraver, at Newcastle on Tyne.

1768 Bewick's first considerable job on wood

commences part publication: Charles Hutton's

"A Treatise on Mensuration".

1771 Works on engravings for children's chap-books. 1774 Apprenticeship ends - returns to Cherryburn

for two years.

1775 Recieved a premium from the Society for the

Encouragement of Arts and Manufactures for

some of his fable illustrations.

1776 Spends three months walking to and around

Scotland. October 1776 travels to London.

1777 Bewick dislikes London despite the openings

there for him: returns to Newcastle. Joins

Ralph Beilby in partnership with brother John

as apprentice.

1785 Bewick's father, mother and eldest sister die. 1786 Marries Isabella Elliot of Ovingham, a

farmer's daughter, whom he has known since

childhood.

1787 First child, Jane, born.

1788 Son, Robert Elliot, born.

1789 Large (for Bewick) engraving of the

Chillingham Bull for Marmaduke Tunstall of

Wycliffe completed.

1790 Publication of "A General History of

Quadrupeds" (first of eight editions in his

lifetime): introduced the vignettes which he

called his tale-pieces. Daughter Isabella

born.

1791 Visits Wycliffe Museum for two months to

commence drawings for "A History of British

Birds".

1793 Daughter, Elizabeth, born.

1795 John Bewick dies.

1797 Volume I of British Birds published (first of

six editions in his lifetime). Partnership

with Beilby dissolved.

1804 Volume II of British Birds published (first of

eight editions in his lifetime). Bewick's son

Robert becomes his apprentice.

1812 Bewick seriously ill. Son Robert becomes his

partner. Begins drawings for "Fables of Aesop"

(published 1818).

1822 Begings writing "Memoir".

1823 Visits Edinburgh and executes first and only

lithographic drawing "The Cadger's Trot".

1826 Wife Isabella dies.

1827 Visited by the American artist and naturalist

Audubon.

1828 Visits London briefly. Dies 8 November aged 75

years.

BEWICK'S METHODS OF WORKING

From an early age Thomas Bewick had a prodigious and natural skill at drawing

... many of my evenings at home, were spent in

filling the flags of the floor and the hearth stone

with my chalky designs. After I had long scorched my

face, in this way, a friend, in compassion, furnished

me with a lot of paper, upon which to execute my

designs - here I had more scope - pen and ink and the

juice of the brambleberry made a good change. These

were succeeded by a Camel hair pencil and shells of

colours and thus supplied I became completely set up

- but of patterns or drawings I had none - the Beasts

and Birds which enlivened the beautiful Scenery of

Woods and Wilds, surrounding my native Hamlet,

furnished me with an endless supply of Subjects.

He had a love of nature and the countryside and he never ceased observing people, animals, birds and trees. John Dovaston confirms this when he describes Bewick as he was in 1827

I found him in very good lodgings ... there were

three windows in the front room, the ledges and

shutters whereof he had pencilled all over with funny

characters, as he saw them pass to and fro, visiting

the well. These people were the source of great

amusement: the probable histories of whom, and how

they came by their ailings, he would humourously

narrate, and sketch their figures and features in one

instant of time. I have seen him draw a striking

likeness on his thumbnail, in one instant; wipe it

off with his tongue, and instantly draw another.

His usual method was to make sketches in watercolour. These are small and delightful works and show a little known side of Bewick. He was a very fine watercolour artist. The watercolour sketch would be small, usually no more than two by three inches depending on the size of the woodblock. He would place the sketch onto the block and fold down the edges so that the paper would be firmly held in place and not move while it was being traced onto the block. In order not to destroy the delicate watercolour drawing with pencil lines the drawing was always reversed. Having transferred the design Bewick or his assistants would start engraving and cutting away unwanted areas. He would use his original watercolour drawing as a guide to tone values, etc.

BEWICK'S WORKSHOP

During his life, Thomas Bewick employed many apprentices. None, however, achived anything like the fame that Bewick himself did.

Bewick's first apprentice was his younger brother, John, who worked with him from 1777 to 1782. Like many of his later apprentices John set out for London and did reasonably well there.

Bewick's apprentices would frequently engrave the work that Thomas had drawn and as the years went on more and more of this sort of work was left to them although Bewick constantly oversaw what they did and frequently touched the blocks up before the printing.

In 1804 Thomas took his son as an apprentice. Although Robert showed some promise, the business of Bewick and Son died in 1849 with him.

In his Memoirs, Bewick writes

I am inclined to think I should have had more

pleasure in working alone for myself, than with such

help as apprentices afforded, for with some of them I

had a deal of turmoil and trouble - and others who

shewed capacity and Genious, and perhaps served out

their time without an interchange of a cross word

between us, yet these, from coming under the guidance

of people in an envious and malignant disposition

perhaps in unison with their own, were, after every

pains and every kindness had been shewn to them, when

done, ready to strangle me.

but in reality it appears that Bewick had many good apprentices as well as mediocre and it is unlikely that he could have found the time to continue working on his vignettes without their help.

------------------------------------------------------- EXCERPT FROM "ORNITHOLOGICAL BIOGRAPHY" BY J.J. AUDUBON 1831

Presently he proposed shewing me the work he was at, and went on with his tools. It was a small vignette, cut on a block of boxwood not more than three by two inches in surface, and represented a dog frightened at night by what he fancied to be living objects, but what were actually roots and branches of trees, rocks and other objects bearing the semblance of men. This curious piece of art, like all his works, was exquisite ... The old gentlemen and I struck to each other, he talking of my drawings, I of his wood cuts. Now and then he would take off his cap, and draw up his grey worsted stockings to his nether clothes; but whenever out conversation became animated, the replaced cap was left sticking as if by magic to the hind part of his head, the neglected hose resumed their downward journey, his fine eyes which afforded me great pleasure ... The tea drinking having in due time come to an end, young Bewick, to amuse me, brought a bagpipe of a new construction, called the Durham Pipe, and played some simple Scotch, English and Irish airs, all sweet and pleasing to my taste.

------------------------------------------------------- LETTER FROM THOMAS BEWICK TO JOHN BAILEY ESQ, Newcastle 25 March 1815

Dear Sir

I herewith send you impressions from the Bank Plate,

which I am very far from being pleased with, after

all the trouble I have been at - I think this little

square with the [pound] 5 has lost me so much more

labout than all the rest of the plate put together

besides the vexation it has caused me - I found,

after Robert had taken out all the spots on all the

letters occasioned by the botched business of the

Aqua fortis, that the [pound] 5 stood up above the

other surrounding parts so as to print "blurry" about

its edges - in attempting to remedy this I was

fearfull that I should quite destroy the white cross

hatching but I found upon rubbing it a little down

that it was very deep, sharp and perfect and looked

better than the impression of it which you got, but

the [pound] & 5 still remained standing up too high

and in my attempts at "mending" this I have failed -

for I know of no way to do this but cutting it down

with a flat tool by which I have lost the brilliant

small white strokes of [pound] 5 as you see by the

Impression and I dare not beat up the plate on the

back of it any more for fear of demolishing the white

cropping altogether - were a broader black line cut

about the [pound] 5 they would then print white but

to do this vexes me because it takes off from the

appearance of a woodcut - But after all these

failures it is some consolation to find that the

scheme itself is perfect and will do - if I can

manage aqua fortis and etch as well as you used to

do, I could then go on "swimmingly" - I wait

anxiously to hear from you to know whether the plate

is liked or not and if it is liked what number will

be wanted from it - I hope you will inform me how Mr

& Mrs Langhorn are - it will give me great pleasure

to know that they are both well - as also Mr Wim & Mr

Nicholas and all friends at Chillingham -

I am

Dear Sir

your obliged obedient

Thomas Bewick

------------------------------------------------------- EXCERPT FROM "JANE EYRE" BY CHARLOTTE BRONTE, 1847

I returned to my book - Bewick's "History of British Birds": the letterpress thereof I cared little for, generally speaking; and yet there were certain introductory pages that, child as I was, I could not pass quite as blank. They were those which treat of the haunts of sea-fowl: of `the solitary rocks and promontories' by them only inhabited; of the coast of Norway, studded with isles from its southern extremity; the Lindeness, or Naze, to the North Cape -

Where the Northern Ocean, in vast whirls, Bouls around the naked, melancholy isles of farthest Thule; and the Atlantic surge Pours in among the stormy Hebrides.

------------------------------------------------------- EXCERPT FROM "THE WATER BABIES" BY CHARLES KINGSLEY, 1863

It was such a stream as you see in dear Bewick; Bewick, who was born and bred upon them. A full hundred yards broad it was, sliding on from broad pool to broad shallow, and broad shallow to broad pool, over great fields of shingle, under oak and ash coverts, past low cliffs of sandstone, and brown moors above, and here and there against the sky and smoking chimney of a colliery. You must look at Bewick to see just what it was like, for he had drawn it a hundred times with the care and love of a true north countryman; and, even if you do not care about your salmon river, you ought, like all good boys, to know your Bewick.

------------------------------------------------------- EXCERPT FROM THE LYRICAL BALLAD "THE TWO THIEVES" OR "LAST STAGE OF AVARICE" BY WORDSWORTH

O now that the genius of Bewick were mine,

And the skill which he learned on the Banks of the

Tyne!

Then the Muses might deal with me just as they chose, For I'd take my last leave both of verse and of prose.

What feats would I work with my magical hand! Book-learning and books should be banished the land: And for hunger and thirst and such troublesome calls, Every ale-house should then have a feast on its walls.

1753 Born at Cherryburn, Eltringham,

Northumberland, to John (farmer and tenant

collier) and Jane Bewick. Eldest of four sons

and five daughters.

1763-67 Attends school of Reverend C. Gregson at

nearby Ovingham Parsonage.

1767 Apprenticed to Ralph Beilby (1743-1817),

engraver, at Newcastle on Tyne.

1768 Bewick's first considerable job on wood

commences part publication: Charles Hutton's

"A Treatise on Mensuration".

1771 Works on engravings for children's chap-books. 1774 Apprenticeship ends - returns to Cherryburn

for two years.

1775 Recieved a premium from the Society for the

Encouragement of Arts and Manufactures for

some of his fable illustrations.

1776 Spends three months walking to and around

Scotland. October 1776 travels to London.

1777 Bewick dislikes London despite the openings

there for him: returns to Newcastle. Joins

Ralph Beilby in partnership with brother John

as apprentice.

1785 Bewick's father, mother and eldest sister die. 1786 Marries Isabella Elliot of Ovingham, a

farmer's daughter, whom he has known since

childhood.

1787 First child, Jane, born.

1788 Son, Robert Elliot, born.

1789 Large (for Bewick) engraving of the

Chillingham Bull for Marmaduke Tunstall of

Wycliffe completed.

1790 Publication of "A General History of

Quadrupeds" (first of eight editions in his

lifetime): introduced the vignettes which he

called his tale-pieces. Daughter Isabella

born.

1791 Visits Wycliffe Museum for two months to

commence drawings for "A History of British

Birds".

1793 Daughter, Elizabeth, born.

1795 John Bewick dies.

1797 Volume I of British Birds published (first of

six editions in his lifetime). Partnership

with Beilby dissolved.

1804 Volume II of British Birds published (first of

eight editions in his lifetime). Bewick's son

Robert becomes his apprentice.

1812 Bewick seriously ill. Son Robert becomes his

partner. Begins drawings for "Fables of Aesop"

(published 1818).

1822 Begings writing "Memoir".

1823 Visits Edinburgh and executes first and only

lithographic drawing "The Cadger's Trot".

1826 Wife Isabella dies.

1827 Visited by the American artist and naturalist

Audubon.

1828 Visits London briefly. Dies 8 November aged 75

years.

BEWICK'S METHODS OF WORKING

From an early age Thomas Bewick had a prodigious and natural skill at drawing

... many of my evenings at home, were spent in

filling the flags of the floor and the hearth stone

with my chalky designs. After I had long scorched my

face, in this way, a friend, in compassion, furnished

me with a lot of paper, upon which to execute my

designs - here I had more scope - pen and ink and the

juice of the brambleberry made a good change. These

were succeeded by a Camel hair pencil and shells of

colours and thus supplied I became completely set up

- but of patterns or drawings I had none - the Beasts

and Birds which enlivened the beautiful Scenery of

Woods and Wilds, surrounding my native Hamlet,

furnished me with an endless supply of Subjects.

He had a love of nature and the countryside and he never ceased observing people, animals, birds and trees. John Dovaston confirms this when he describes Bewick as he was in 1827

I found him in very good lodgings ... there were

three windows in the front room, the ledges and

shutters whereof he had pencilled all over with funny

characters, as he saw them pass to and fro, visiting

the well. These people were the source of great

amusement: the probable histories of whom, and how

they came by their ailings, he would humourously

narrate, and sketch their figures and features in one

instant of time. I have seen him draw a striking

likeness on his thumbnail, in one instant; wipe it

off with his tongue, and instantly draw another.

His usual method was to make sketches in watercolour. These are small and delightful works and show a little known side of Bewick. He was a very fine watercolour artist. The watercolour sketch would be small, usually no more than two by three inches depending on the size of the woodblock. He would place the sketch onto the block and fold down the edges so that the paper would be firmly held in place and not move while it was being traced onto the block. In order not to destroy the delicate watercolour drawing with pencil lines the drawing was always reversed. Having transferred the design Bewick or his assistants would start engraving and cutting away unwanted areas. He would use his original watercolour drawing as a guide to tone values, etc.

BEWICK'S WORKSHOP

During his life, Thomas Bewick employed many apprentices. None, however, achived anything like the fame that Bewick himself did.

Bewick's first apprentice was his younger brother, John, who worked with him from 1777 to 1782. Like many of his later apprentices John set out for London and did reasonably well there.

Bewick's apprentices would frequently engrave the work that Thomas had drawn and as the years went on more and more of this sort of work was left to them although Bewick constantly oversaw what they did and frequently touched the blocks up before the printing.

In 1804 Thomas took his son as an apprentice. Although Robert showed some promise, the business of Bewick and Son died in 1849 with him.

In his Memoirs, Bewick writes

I am inclined to think I should have had more

pleasure in working alone for myself, than with such

help as apprentices afforded, for with some of them I

had a deal of turmoil and trouble - and others who

shewed capacity and Genious, and perhaps served out

their time without an interchange of a cross word

between us, yet these, from coming under the guidance

of people in an envious and malignant disposition

perhaps in unison with their own, were, after every

pains and every kindness had been shewn to them, when

done, ready to strangle me.

but in reality it appears that Bewick had many good apprentices as well as mediocre and it is unlikely that he could have found the time to continue working on his vignettes without their help.

------------------------------------------------------- EXCERPT FROM "ORNITHOLOGICAL BIOGRAPHY" BY J.J. AUDUBON 1831

Presently he proposed shewing me the work he was at, and went on with his tools. It was a small vignette, cut on a block of boxwood not more than three by two inches in surface, and represented a dog frightened at night by what he fancied to be living objects, but what were actually roots and branches of trees, rocks and other objects bearing the semblance of men. This curious piece of art, like all his works, was exquisite ... The old gentlemen and I struck to each other, he talking of my drawings, I of his wood cuts. Now and then he would take off his cap, and draw up his grey worsted stockings to his nether clothes; but whenever out conversation became animated, the replaced cap was left sticking as if by magic to the hind part of his head, the neglected hose resumed their downward journey, his fine eyes which afforded me great pleasure ... The tea drinking having in due time come to an end, young Bewick, to amuse me, brought a bagpipe of a new construction, called the Durham Pipe, and played some simple Scotch, English and Irish airs, all sweet and pleasing to my taste.

------------------------------------------------------- LETTER FROM THOMAS BEWICK TO JOHN BAILEY ESQ, Newcastle 25 March 1815

Dear Sir

I herewith send you impressions from the Bank Plate,

which I am very far from being pleased with, after

all the trouble I have been at - I think this little

square with the [pound] 5 has lost me so much more

labout than all the rest of the plate put together

besides the vexation it has caused me - I found,

after Robert had taken out all the spots on all the

letters occasioned by the botched business of the

Aqua fortis, that the [pound] 5 stood up above the

other surrounding parts so as to print "blurry" about

its edges - in attempting to remedy this I was

fearfull that I should quite destroy the white cross

hatching but I found upon rubbing it a little down

that it was very deep, sharp and perfect and looked

better than the impression of it which you got, but

the [pound] & 5 still remained standing up too high

and in my attempts at "mending" this I have failed -

for I know of no way to do this but cutting it down

with a flat tool by which I have lost the brilliant

small white strokes of [pound] 5 as you see by the

Impression and I dare not beat up the plate on the

back of it any more for fear of demolishing the white

cropping altogether - were a broader black line cut

about the [pound] 5 they would then print white but

to do this vexes me because it takes off from the

appearance of a woodcut - But after all these

failures it is some consolation to find that the

scheme itself is perfect and will do - if I can

manage aqua fortis and etch as well as you used to

do, I could then go on "swimmingly" - I wait

anxiously to hear from you to know whether the plate

is liked or not and if it is liked what number will

be wanted from it - I hope you will inform me how Mr

& Mrs Langhorn are - it will give me great pleasure

to know that they are both well - as also Mr Wim & Mr

Nicholas and all friends at Chillingham -

I am

Dear Sir

your obliged obedient

Thomas Bewick

------------------------------------------------------- EXCERPT FROM "JANE EYRE" BY CHARLOTTE BRONTE, 1847

I returned to my book - Bewick's "History of British Birds": the letterpress thereof I cared little for, generally speaking; and yet there were certain introductory pages that, child as I was, I could not pass quite as blank. They were those which treat of the haunts of sea-fowl: of `the solitary rocks and promontories' by them only inhabited; of the coast of Norway, studded with isles from its southern extremity; the Lindeness, or Naze, to the North Cape -

Where the Northern Ocean, in vast whirls, Bouls around the naked, melancholy isles of farthest Thule; and the Atlantic surge Pours in among the stormy Hebrides.

------------------------------------------------------- EXCERPT FROM "THE WATER BABIES" BY CHARLES KINGSLEY, 1863

It was such a stream as you see in dear Bewick; Bewick, who was born and bred upon them. A full hundred yards broad it was, sliding on from broad pool to broad shallow, and broad shallow to broad pool, over great fields of shingle, under oak and ash coverts, past low cliffs of sandstone, and brown moors above, and here and there against the sky and smoking chimney of a colliery. You must look at Bewick to see just what it was like, for he had drawn it a hundred times with the care and love of a true north countryman; and, even if you do not care about your salmon river, you ought, like all good boys, to know your Bewick.

------------------------------------------------------- EXCERPT FROM THE LYRICAL BALLAD "THE TWO THIEVES" OR "LAST STAGE OF AVARICE" BY WORDSWORTH

O now that the genius of Bewick were mine,

And the skill which he learned on the Banks of the

Tyne!

Then the Muses might deal with me just as they chose, For I'd take my last leave both of verse and of prose.

What feats would I work with my magical hand! Book-learning and books should be banished the land: And for hunger and thirst and such troublesome calls, Every ale-house should then have a feast on its walls.

![Fishing - [Man Sitting On Bank Fishing] Tailpiece to the Great White Heron, History of British Birds Vol II; Thomas Bewick; 1804; 1972/47/16](https://collection.waikatomuseum.org.nz/records/images/medium/4553/f9490f6f1d324474803d333604af77b47f7629be.jpg)

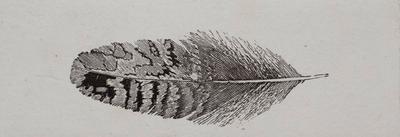

![Claw [Claw with Brush and Pallet] Tailpiece to Shoreler, History of British Birds; Vol II; Thomas Bewick; 1804; 1972/47/17](https://collection.waikatomuseum.org.nz/records/images/medium/4554/9774bb8bf0ec6a87daa44ab9b51c4565dae8b74b.jpg)

![Fables [Domestic Scene Mother and Sick Child]tailpiece to Of the Auk, or Penguin, Hist Brit Birds Vol II (6th ed); Thomas Bewick; 1826; 1972/47/18](https://collection.waikatomuseum.org.nz/records/images/medium/4555/e206478b66612f55c5d5ec8d2a8e9785eb1f3c2f.jpg)

![Fable - [The Work Of The Devil] Tailpiece to Little Auk, History of British Birds Vol II; Thomas Bewick; 1804; 1972/47/19](https://collection.waikatomuseum.org.nz/records/images/medium/4556/aad99ee38f820ded9423427d176c2b2c08a55d72.jpg)

![[Man Resting Beside Stream]; Tailpiece to the Bimaculated Duck History of British Birds Vol II (6th)?; Thomas Bewick; 1804; 1972/47/4](https://collection.waikatomuseum.org.nz/records/images/medium/4559/81a0f55759929a9c1e177927b68c024a80021300.jpg)